The Ordnance Survey of Ireland

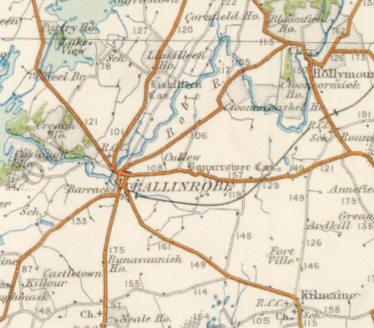

The Ordnance Survey of Ireland (1829 – 1842) was the first large-scale survey of an entire country in the world. Acclaimed for their accuracy, these maps are regarded as among the finest ever produced. For the family historian, they can identify the lay of the land in the decades preceding the famine and, most importantly, the homes that had been vacated by the time of Griffith’s Primary Valuation.

Particularly relevant for genealogy or those with an interest in the history of a place, these “6-inch” maps include every tiny house or cabin that was likely occupied before the Famine. The good news is that the OSI has captured this and later mapped data in a digitised format, and they are free to inspect online.

A short history of the Ordnance Survey in Ireland

Copied from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.charlesclosesociety.org/files/Irelandto1922.pdf

Ireland within the United Kingdom: 1824-1922

As in Britain, the formal start of identifiably ‘Ordnance Survey’ work in Ireland was preceded by a military survey that, with the wisdom of hindsight, can be seen as a forerunner. Between 1776 and 1790 General Charles Vallency (c.1726-1812) mapped most of Ireland south of a line from Arklow to Limerick: this was part of a larger, apparently unfulfilled scheme, for mapping the southern half of the country. Scales employed were about 1:20,160 and 1:40,320. As with the military survey of Scotland, it remained in manuscript. As in Britain, around this time several counties were surveyed and published commercially at 1:63,360 or larger scales: as in Scotland, these surveys by no means covered the whole country. At this time Ireland still had a measure of independence, and its own parliament: by the Act of Union in 1800 it became part of a larger United Kingdom.

The coming of the Ordnance Survey to Ireland appears to have been at the first instance in response to a request from the Lord-Lieutenant, early in 1824: a few months later a select committee of the UK House of Commons considered the matter. The valuations which underlay the territorial system of taxation were based on hopelessly obsolete information, and it was necessary for the boundaries of the townlands – divisions averaging three hundred to six hundred acres (about 120 to 240 hectares) each – to be mapped accurately in order to provide a framework for the new valuation. Presumably the Board of Ordnance had already decided to produce a 1:63,360 map of the country, and the original scheme, recommended by the Select Committee in June 1824, was to make a six-inch (1:10,560) survey of townland boundaries and of such details as could be shown on a 1:63,360 map. Instead, Colonel Thomas Colby, the head of the Ordnance Survey, ordered that all details should be mapped with as much accuracy as the 1:10,560 scale permitted, except for field boundaries, and after a few years they too were being mapped. The early years of the Irish survey were clouded by the need to repeat much unsatisfactory work: the first county to be published was (London) Derry, in 1833. By the late 1830s work was progressing smoothly. Publication had not originally been envisaged, but was found to be economical compared with producing the needed multiple copies by hand. The standard sheet size was equal to 32,000 × 21,000 feet (6.06 × 3.98 miles; about 9.75 × 6.40 km) on the ground. It was soon found that the six-inch was inadequate for larger urban areas, and after trying various larger scales, the five-foot scale (1:1056) was adopted. Except for Dublin, engraved experimentally in 1841-51, these 1:1056 surveys remained in manuscript. Most of the workers on the Irish survey – over 2000 at its peak – were locally-recruited civilians, but they were under military supervision, by officers and men of the Royal Engineers and the Royal Sappers and Miners. Field operations were completed in 1841-2, and much of the labour force was transferred to Britain, for six-inch survey there.

As well as producing maps, the Irish survey also generated written matter: Colby directed that the officers were to keep journals and write memoirs covering a wide variety of what would today be termed sociological, environmental, economic and historical information. Only one of these memoirs, for the parish of Templemore in County Derry (containing the city of Londonderry), was published, in 1837, and as the survey progressed southwards so the memoir material became more and more scanty, with the result that there was nothing for the more southerly part of the country. The Templemore memoir was costly to prepare, and this contributed to the demise of the project. The raw material for the memoirs was subsequently transferred to the Royal Irish Academy, and has provided the text for considerable number of the Ulster memoirs which have been published since the 1980s. In the short term, the most tangible result of the memoir project was geological: a map and accompanying text for County Derry were issued in 1843, and the embryonic organisation in Ireland was a constituent of the newly separated Geological Survey of the United Kingdom created in 1845. The historical work, which was in part related to the desirability of obtaining authentic forms for place-names, proved controversial, and contributed to the demise of the enterprise: though many of those responsible were perhaps more unionist than nationalist in outlook, the material they collected was a contribution to a revival of national consciousness.

By 1842 the field survey was finished, and the engraving and publication of the six-inch maps was completed late in 1846. By that time Ireland was in the grip of famine, and not the least of the achievements of the survey was the mapping of Ireland on the eve of that catastrophe. Another achievement was to provide a model for Great Britain: large-scale published national survey has perhaps been one of Ireland’s more underrated exports. In 1846 there was the possibility that the whole OS organisation in Ireland would be dismantled, but two things averted this: the desirability of contouring and of revising the northern counties so as to add the field boundaries – and, as it turned out, to record the landscape changes consequent upon the Famine. Contouring had been tried experimentally in the Inishowen peninsula in County Donegal in 1839, and seemed worth persisting with. Both contouring and revision were affected by under-funding: contouring was abandoned in 1857, and by the late 1880s only the north-eastern half of Ireland had been revised. The one-inch map was belatedly begun in 1851, largely in response to geological pressures: the outline version was published between 1855 and 1862, but the hachured hills version was only completed in 1895.

Unlike in Britain, there was a solid justification for the large-scale mapping of Ireland: its uses for tenement valuation, under the General Valuation Office, which needed periodic revision and refinement. For this reason from 1855 a number of towns were mapped at 1:500, independent of county revision, and County Dublin was resurveyed at 1:2500 in 1863-7. Some further isolated 1:2500 surveys were made for the Landed Estates Court. By the mid-1880s the six-inch was seen to be inadequate and the completion of the resurvey at 1:2500 of southern Britain facilitated the start of remapping of Ireland at that scale. The work began, quite literally, in the middle of County Roscommon in 1888: the northern half was revised at six-inch, the southern half was remapped at 1:2500. The general pattern of work was west to east, with priority for those counties not revised at six-inch: the last counties to be completed, in 1913, were Westmeath and the northern half of Roscommon. Work proceeded rather more slowly than with the original six-inch survey: the sheets were laid out as sixteen sub sheets equal to 8,000 × 5,250 feet (1.515 × 0.994 miles; about 2.43 × 1.60 km) on the ground, within the existing six-inch sheet lines, and mountain and moorland areas were revised at six-inch, and not mapped at the larger scale. Publication of the 1:2500 of Ireland was completed by the end of August 1914: by that time revision was under way. The remapping at 1:2500 was accompanied by completion of the contouring. Though the 1:1056 and 1:500 were not revised after 1894, 1:1056 photo-enlargements from the 1:2500 were produced for valuation purposes for a great many towns and larger villages: in this Ireland anticipated the 1:1250 enlargements produced in Britain from 1911 onwards.

As in Britain, from the 1890s the one-inch was revised independently of the larger scales, and by 1918 Ireland was covered by a coloured one-inch, based on a revision of 18981901, a one-inch outline map, partly revised 1898-1901 and partly revised 1908-14, and quarter-inch and half-inch maps: the last was a much more finished affair than the earlier corresponding mapping of Britain.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page