14 Margaret Gibbons, Ballinrobe & Australia

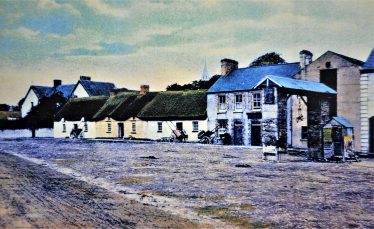

Margaret Gibbons was born c 1822/29 (age on records range from 18 to 25) in Ballinrobe, great, great, grandmother of Rosalie Darby who contacted me in 2016 trying to trace the families roots in Ballinrobe, approximately 190 years from when this story started.

Margaret had two brothers John and Thomas and four sisters Caith, Maria, Bridget and Ann; there is as yet no record of her parents’ names. Margaret was possibly married to a Patrick Duffy and they had a child also named Patrick of 13 months when she was transported on the three masted ship Kenner to Van Diemen’s Land now Tasmania.

Trial at Ballinrobe Courthouse

Margaret was tried and convicted at Ballinrobe Courthouse on 15th June 1847 at the height of the famine for supposedly stealing a lamb (if you even petted a lamb that was considered theft) at the Common, now the Cornmarket in Ballinrobe. She was acquitted of stealing a blanket and sentenced for 10 years and transportation. Irish girls/women often committed offences to gain admittance to jail (where they would receive some food) due to starvation or, being unable to gain admittance to workhouses. Frequently most of their parents, brothers and sisters were dead after being evicted from their small land-holding.

Transportation

If young women received a prison sentence they also risked transportation at that time as the British were keen to have more ‘breeding stock’ and workers in their colonies. The idea of transportation would have been frightening but better than death from starvation. Some might have had a sense of danger as well as the idea of travelling to the new world, where new possibilities might be achieved. The climate was different, the surrounding environment unfamiliar, the plants and animals and even the light seemed different according to come convict letters. Over 30,000 men and 9,000 women were transported directly from Ireland.

Sentence & Training

After sentencing convicts were not allowed to remain ‘a drain’ in the local jails but would be speedily removed to Grangegoman Depot in Dublin, the first exclusively female prison in the British Isles, to await transportation. About fifty cells were used exclusively for these convicts. They did not mix with ordinary prisoners. They exercised and ate separately and received basis employment training in certain skills so that they could be more productive and easily find work; they would remain at work until they had served their sentence and paid their debt to society

By the 1850s, the death penalty was restricted to murder and treason, and public executions ended in 1866. The lesser physical penalties were also curtailed or abolished; branding in 1779, the pillory in 1837 and whipping of women in 1819.

What did Margaret bring with her?

Apart from her beloved son Margaret would have had no personal effects. She would have been given some clothing at Grangegorman but one possession she did have was the memory of the songs and poems she would have learnt during her happier days in Ireland. These were the precious memories many convicts brought with them to their new land.

Her Son

The Grangegoman Depot records show Margaret was retained there with her child on 17th November, 1847. These records state that she was single, could not read or write and had no trade. She was finally ‘disposed of’ together with her son on the convict ship The Kenner, a three-masted ship, on 16th June 1848 together with 144 female convicts and 34 children.

It was in the establishment’s interest to have as many children as possible sent off in order to avoid their becoming chargeable on the rates, under pressure from the Grand Juries. Many children were transported with their mothers and even in some cases with their fathers. The main preoccupation was to dispose of them in the cheapest way, whether on board ship or otherwise. In the period from its opening in 1836 up to 1853 a total of 3,196 women were transported from the Grangegorman Depot. The Kenner arrived in Hobart, Tasmania on 7th October 1848 after a 15 week voyage.

Leaving Grangegorman

The journey from Dublin to Kingstown, formerly a major port of entry from Great Britain, took by hours by jaunting cars, which was miserable in wet weather. There would be a military escort to guard the women because of their possible escape at this sensitive time of departure from their native land.

The Ship

On boarding the prison ship The Kenner they were formally handed over to the Master. They would have been checked by a surgeon and directed by a matron to below deck to their rather miserably small cramped prison quarters with each woman being allowed a berth separated by planks; so narrow that a woman with an infant could not sleep in one without danger. There was no consideration given to nursing mothers. Some might have been confined behind bars and others forced to sleep in hammocks. A few may have been restrained in chains and only allowed on deck for fresh air and exercise. The food would have been welcome but shortages of water frequently occurred.

A Long Voyage

The long voyage to Australia could take up to 4 to 6 months depending on the weather, lack of wind and whether there was any infectious diseases on board; they would not have been allowed berth in ports to pick up fresh water and provisions until the danger of infection had passed. Cruel masters, on some ships with harsh discipline, scurvy, dysentery and typhoid resulted in frequent fatalities on some ships.

Much suffering would have been experienced by the women with five deaths and according to the surgeon’s records several children died from the harsh conditions, sea-sickness, tough regimes and confinement plus scarcity of fresh water and food. Many of these women would never have seen the sea, not to mind the experience of dark cramped spaces being rolled around by waves and storms below deck. They must have been terrified. Patrick was not recorded on the surgeons list so it is assumed he landed with his mother.

Arrival in Tasmania

On arrival in Hobart the convicts would have been transferred to the custody of the Governor of the colony in which they arrived. Indents or Indentures were the documents used to record this transaction on arrival. Margaret had been placed on the HMS Anson. This was a 1,870 ton warship which arrived in Hobart in 1844 landing 499 male convicts. After disembarking her ‘cargo’ she was refitted as a prison-ship and towed to Prince of Wales Bay, Risdon, near Hobart. Conditions were tough on board but fair with an excellent level of cleanliness and, besides the necessary duties of washing and cooking, training for their future roles included needlework, the manufacture of shoes, straw-hats and door mats, bonnets, shifts, socks, aprons, sheets etc.[1]

When the women had completed their six-month probation they were hired out into service as ‘probation’ pass-holders. Pass holders could earn wages and in some cases higher wages and living better conditions than they ever could have hoped to do in Ireland.

Separation from Son

However, sadness must have been experienced when children were separated from their mothers at two years of age or when mothers were assigned to the Anson; a lonely and sad Patrick was probably sent to one of the nurseries; a record shows that he died at 5 years.

Work

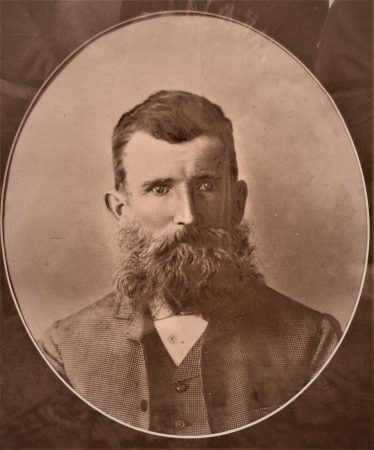

Having survived the hardships Margaret was appointed as a house-maid in Hobart and she quickly sought permission to marry three times which was normal at the time. She was finally allowed to marry John Gill, who was also transported as a convict for stealing some boots with a sentence of 7 years. They married on the 7th April 1851.

Ticket of Leave

Margaret received her ticket of leave on 6th March, 1852, her conditional pardon on 8th August 1853 and a free pardon on 4th April, 1854. She was finally a free woman after obvious good behaviour and working hard to achieve her goal of survival and freedom.

Family

Margaret and John Gill’s daughter, Mary Ann Gill was born on the 14th August 1852 and the record lists her father as a shoemaker. The following year on 17th August 1853 a notice appeared in the newspaper The Courier of Hobart with a request from Gill stating;

I, John Gill, hereby give notice that my wife, Margaret Gill, has left my residence, in Murray Street Hobart Town without my will and consent, and has gone to Melbourne with George Armstrong. Any one giving information of their whereabouts will be handsomely rewarded. And I further caution George Armstrong, if still with him, to give her up immediately, to save any legal proceedings. He was obviously unsuccessful in tracing her.

Descendants and Remarriage

Margaret must have stayed on the Australian mainland as her daughter Mary Ann, was in Victoria in 1867 when she married John Carter in Dunkeld; they had 11 children (8 sons and 3 daughters). Their son Russell was Rosalie’s grandfather (see below).

While some inter-generational trauma passing down the family line they were a brave and courageous people who worked hard to make a better life for their children. Margaret’s grandsons and great grandsons served in World War 1 and WW II. Margaret’s great-great-grandson Stan won a Military Medal and another brother Alan was captured in Singapore and, as a prisoner of the Japanese army, he worked on the Thai Burma Railway and died while being transported to Japan.

The son Russell mentioned above was Rosalie’s maternal grandfather. He married Lily Malcolm and had five children (3 sons and 2 daughters). Their daughter Joyce Carter had two daughters Anne and Rosalie who contacted us.

Margaret’s great-granddaughter is now 95 years (Rosalie’s Mom) and will be pleased that her great grandmother’s story is being told, particularly back in the very town of Ballinrobe where the story began over 172 years ago at a time of devastating famine, death and disease.

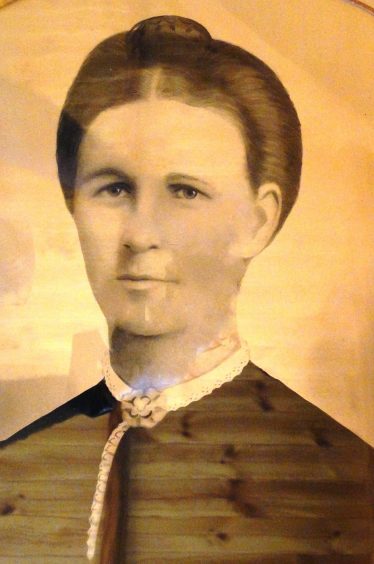

Rosalie Darby, Margaret’s great, great, granddaughter supplied details of Margaret’s life and photographs for this article for which we are very grateful.

[1] The Hobart Town Courier, 29 October 1844, p 2

No Comments

Add a comment about this page